This article is about the design and construction of a wind tunnel by students Daniel, Kavel, Alex and Harry.

Overview

Over the past year, whilst studying for our A-levels, we have been constructing a wind tunnel. Intended to be operated by students, it is for testing the aerodynamics of their miniature car models, such as F1 in Schools cars, whilst also enriching and inspiring their learning. In addition, the wind tunnel has a modular design so that sections can be easily replaced or modified to increase its capabilities. It features over a thousand screws, is 3m long and has a testing speed of 15m/s.

We would like to sincerely thank Accu, for supplying us with high quality fasteners, and the schools DT department for their support in helping bring this project to life.

Introduction

We initiated this project towards the end of Year 12 thinking it would be something fun, which we could gain technical and practical experience from, to complete in the summer holiday. (In hindsight, this timeframe was a severe underestimation.) Furthermore, members Daniel and Kavel had recently finished an extensive stint in the F1 in Schools competition which helped provide us with the idea that we could make something for new students wanting to compete. F1 in Schools is an international STEM event for high school students where they design and race a 20cm long car for their own mini version of an F1 team. After a round of regional and national competitions the best teams make it to the coveted World Finals which have been hosted in locations such as Singapore and Austin.

Example of F1 in Schools cars at the 2023 World Finals hosted in Singapore.

Designing

The design process started by identifying what we were going to put into the wind tunnel, in a part called the test section. This was F1 in Schools cars. How fast should the air be moving in the test section? Well, F1 in Schools cars hastily race down a 20m track in around a second so have an average speed of 20m/s. The frontal area of the car, which we know on average, should be at most 10% the cross-sectional area of the test section. Multiplying the wind speed by the area it is moving through gives us the volumetric flow rate, which is the volume of air that passes through an area in a second. Knowing this, we could find a suitable fan to build our wind tunnel around. In the end, to save on costs, we selected a fan that would give us a test section speed of 15m/s.

Since we now know the diameter of the fan, we were able to design the diffuser and contraction cone. The diffuser is the very long structure rearward of the test section, responsible for reducing turbulent air, and the contraction cone is the short, curved, conical shaped structure in front of the test section, responsible for smoothly reducing a large volume of slow-moving air into a smaller volume so that the air travels much faster, at 15m/s to be precise. Determining the curvature of the contraction cone was a bit complicated as it involved solving a complex differential equation.

Labelled drawing of the wind tunnel.

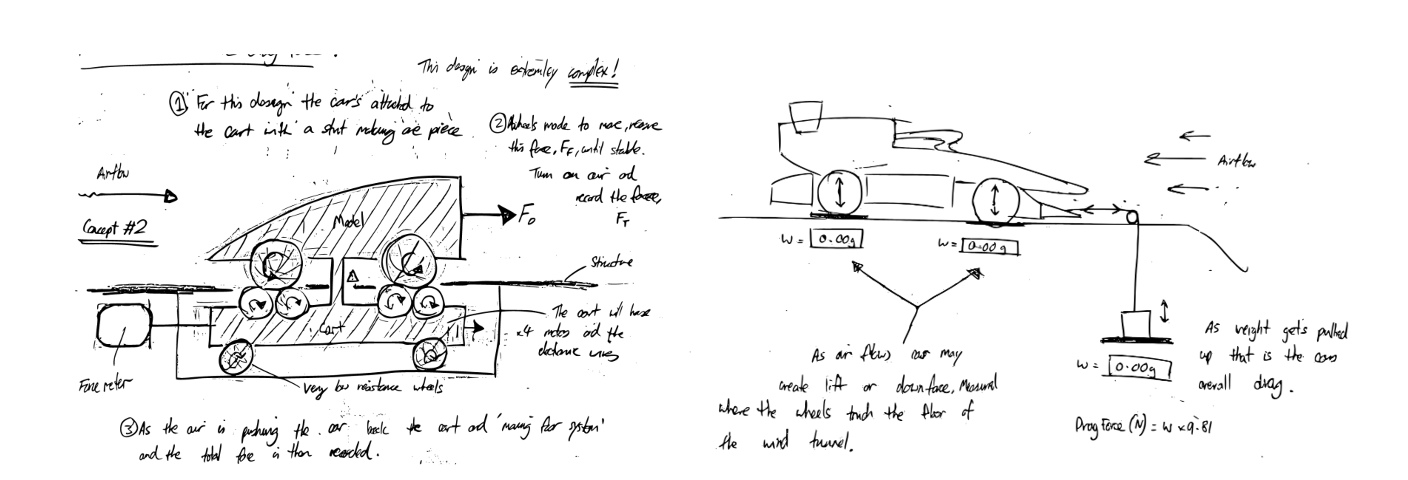

Arguably the most complex part of the wind tunnel is the test section. This is where electrical components measure data about the aerodynamic properties of the car, vital information for a student engineer trying to improve their design. To do this, various solutions were proposed. One was very complex and seemingly impossible to manufacture, not to mention expensive, another was relatively simple but still somewhat useful and then there was the one we finally decided upon, which struck a balance between everything we needed.

This solution measures the overall drag force and the downforce about the front and rear wheels. It achieves this by using three small devices called load cells, which detect the forces applied by the car which is just a result of the moving air applying a force onto the car. Each load cell features strain gauges which are small sensors that contain a thin metallic wire that changes its electrical resistance when deformed by an applied force. This is because resistance depends on the length and cross-sectional area of the wire. As the strain gauges deform easily, the resistance is something we measure, having previously calibrated the load cells, to determine the force applied. This process is handled computationally using analogue-to-digital converters and a Raspberry Pi microprocessor.

Sketches of test section ideas.

Building

Having finalised the majority of the wind tunnels design we could start bringing it to life. Also, since we’ve just started the next school year manufacturing shouldn’t take too long right, say a month and we’ll be done.

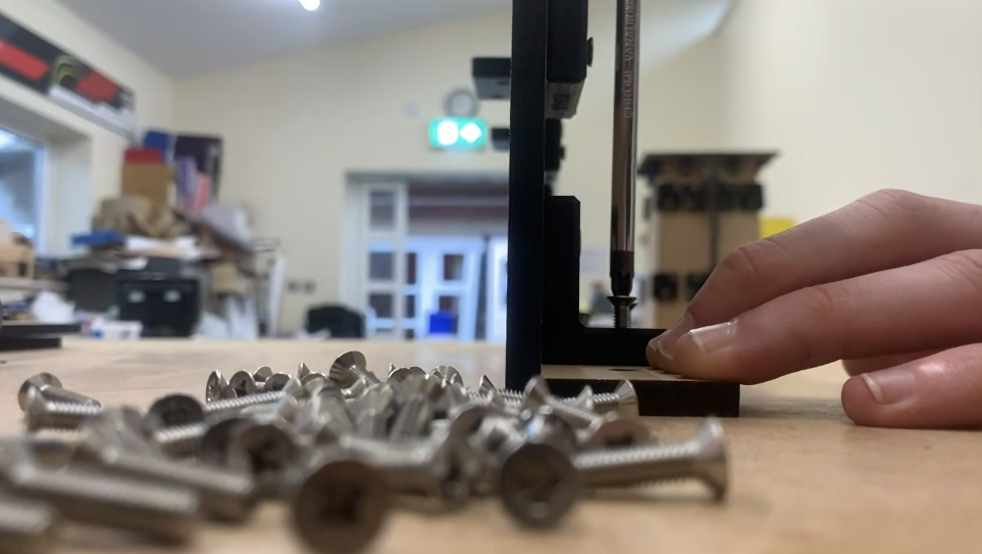

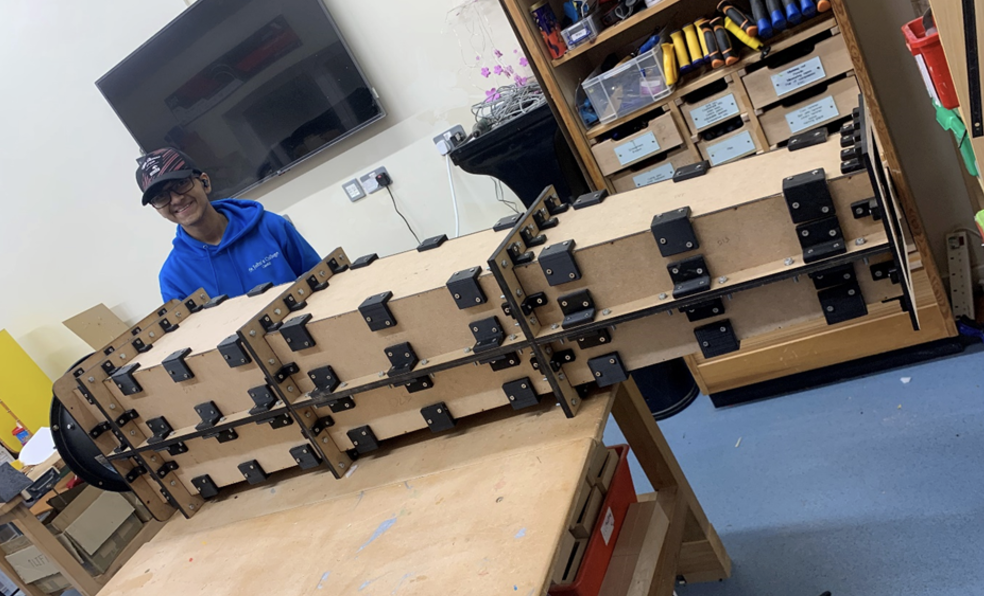

We started with laser cutting the many MDF panels that makeup the bodywork of the wind tunnel whilst simultaneously 3D printing the 352 brackets that would help hold the panels together. Then, using a soldering iron with a custom press device, we slowly and precisely melted 1,166 brass inserts into the holes of the brackets providing them with a strong thread to put screws through. Next, we began assembling sections of the wind tunnel by screwing the brackets and panels together which was a mostly calming and satisfying process as we saw the tunnel quickly taking shape. However, there were a couple of errors with certain parts meaning they had to be remade.

Connecting the panels together with brackets and Accu’s screws.

The ‘mock’ assembly of the diffuser section.

Next, having transferred all the parts into Kavel’s parents’ garage, we applied wood filler into the small dips and crevices present on the wind tunnel's surfaces and once dry sanded them all back. After two rounds of this process, to get it near perfect, we then applied two to three layers of primer and once this dried, we sanded the surfaces back once more. Then, we sprayed on a couple of layers of black and white paint to add some colour which was followed by attaching water slide decals of our wonderful sponsors and then finished with a layer of a clear topcoat.

This part of the process, despite being succinctly summarised into a single paragraph, disguises how long this took us. In reality the wind tunnel's large size meant it had a very large surface area so sanding and painting, particularly difficult next to the brackets, took much longer than we could have predicted. We got pretty exhausted spending hours on the floor, working on the tunnel, whilst outside it got cold and dark, but in the end, we finished it and we’re very happy with the result.

A section of the wind tunnel we haven’t mentioned yet is the flow straightener, also referred to as the honeycomb, which is situated in front of the contraction cone. The flow straightener is an array of small channels that help evenly distribute the energy of the incoming air to create a smooth, laminar flow. Not wanting to spend over £100 on outsourcing a honeycomb we decided that it was best to manufacture one ourselves. We experimented with cutting down plastic straws and glueing them together but quickly realised this was ineffective and very time consuming, so we opted to use 3D printing. This was because it is an automated process, which doesn’t require many manual work hours, and is incredibly precise.

Finally, everything was ready to be assembled. The sections were bolted together and in between them we placed custom rubber seals to help achieve a near airtight environment. Then we connected the electronics together and attached them to the underside of the test section. And that was that. We could finally take a step back, turn the wind tunnel on and see how it works, a very exciting moment indeed.

Final checks of the wind tunnel before its first test.

Despite the wind tunnel taking a long time to finish, mainly because we were studying for our A-level so only worked on it in our spare time, it was complete and working well.

Wind Tunnel Construction Video

The Future

We have decided to donate the wind tunnel to the school as we hope it can help students learn and importantly provide a source of inspiration so that they can go on to achieve much more impressive feats. It’s open to any interested students in both the senior school and sixth form and we welcome anyone to try and improve the wind tunnel's design.

Kavel, Daniel and Harry are now all studying for their first year in engineering at university and Alex has recently applied to study engineering at university as well.

Mrs Crowley-Davies (DT teacher) says, “What an achievement! It has been a pleasure to assist the team in any way we could. The boys have been motivated and driven to produce such a fantastic piece of engineering that not only reflects their skills and interests, but also acts as a legacy to benefit the F1 in Schools teams that are following in their footsteps. They continue to impress and make our school proud."

The wind tunnel being used to test a team's car.

Once again, we would like to thank the support of Accu and the schools for their support and we hope the wind tunnel serves future students well.

Accu: https://www.accu.co.uk/

F1 in Schools: https://www.f1inschools.com/

Daniel, Kavel, Alex and Harry.